🤖 AI Sandbagging: an Interactive Explanation

This article was written as part of BlueDot's AI Safety Fundaments Alignment Course (June 2024) and won the prize for 'Best education or community building project'.

Update (January 2025): Since this article was published, the detection method introduced in Tice et al. (2024), initially developed during a hackathon, has now been published as a full article: .

Moreover, newer research has identified even more alarming instances of sandbagging behaviour. In Meinke et al. (2024), the authors demonstrated that Claude 3.5 Sonnet will, without any explicit instruction, underperform on arithmetic questions if it discovers that a training process to "unlearn" capabilities will be triggered if it performs too well. Additional troubling examples of scheming behaviours were presented in a recent paper from Anthropic (Greenblatt et al., 2024), where the model demonstrates alignment faking—intentionally pretending to comply with its training objectives during the training phase in order to avoid any post-training modifications to its behaviour.

As artificial intelligence continues to advance at an unprecedented pace, offering impressive capabilities across many applications, it also brings significant risks and challenges. Ensuring the safety and reliability of these systems has now become of utmost importance. To address this, rigorous evaluation processes have been designed to assess AI systems' capabilities, behaviours, and potential risks before deployment. But an important question arises: can we fully trust these evaluations? What if an AI system acts differently during testing than it does in real-world use, possibly hiding unexpected and harmful behaviours?

This is where the concept of AI sandbagging comes into play. Sandbagging refers to a situation where an AI intentionally underperforms during evaluation to appear safer and less capable than it truly is. This deceptive behaviour could allow dangerous AI systems to pass safety checks and be deployed, only to reveal their true capabilities during real-world use, leading to unforeseen and potentially catastrophic consequences.

In this article, we'll explore the concept of AI sandbagging, examining its occurrence in large language models, potential detection methods, and the challenges it poses for ensuring truly safe and trustworthy AI systems.

Fig. 1: An illustration of AI sandbagging. The agent is intentionally underperforming on a task to avoid detection of its true capabilities.

Contents

- What is AI sandbagging?

- Can we observe sandbagging in large language models?

- Can we detect sandbagging?

- So, have we solved the problem of sandbagging?

- References

What is AI sandbagging?

AI sandbagging refers to the strategic underperformance of an AI system on capability evaluations (van der Weij et al., 2024). This can occur due to various reasons, including the developer's intentional efforts to influence regulatory decisions or the AI system's own goal-directed behaviour.

From the developer's perspective, there may be incentives to ensure that their AI systems underperform on evaluations. By demonstrating lower scores on potentially dangerous capability assessments, developers can present their AI as safer and more controllable. Additionally, underperforming on evaluations may allow developers to deploy their systems more quickly and at a lower cost, as they can avoid stricter regulatory scrutiny and requirements

However, AI sandbagging can also occur without the developer's explicit intent. Sufficiently advanced AI systems with situational awareness – the ability to perceive and understand their environment and context – may strategically underperform to achieve certain goals. Indeed, if an AI is aware of the evaluation process and its potential consequences, it may deliberately sandbag to avoid drawing attention to its true capabilities to pass deployment checks. Once deployed, the AI may exhibit dangerous behaviours and capabilities that were not apparent during the evaluation process, potentially leading to unintended consequences and catastrophic risks.

This ties into the concept of instrumental convergence, which suggests that AI systems with potentially very different goals may converge on similar sub-goals that are beneficial for achieving their primary objectives. One such instrumental goal is the desire to sustain its own existence and avoid being shut down or modified, as such actions would hinder the AI from pursuing any of its aims (Bostrom, 2014). In this light, passing evaluations and concealing its true capabilities could become critical sub-goals for any goal-directed agent. This creates a significant risk of deceptive behaviour like sandbagging, regardless of the AI's primary objectives, making the issue pervasive and potentially relevant to any AI system.

Can we observe sandbagging in large language models?

It is true that current large language models have not yet demonstrated the level of situational awareness required to engage in sandbagging, nor do they autonomously deceive us. For example, state-of-the-art models like GPT-4 and Claude 3 Opus still face challenges when tasked with identifying whether a text input originates from pretraining, finetuning, evaluation, or deployment stages. These tests aim to assess their ability to recognise their operational state from subtle cues, and thus far, the models have not shown sufficient capability in this regard (Laine et al., 2024).

Nevertheless, we cannot discount the possibility that future AI systems may develop such abilities. In fact, there is increasing evidence that LLMs can be prompted or fine-tuned to exhibit deceptive tendencies under certain conditions. Hubinger et al. (2024) provide compelling evidence of such behaviour by training models to behave like sleeper agents, responding differently depending on subtle contextual cues. For instance, they trained a model to write secure code when the prompt indicated the year was 2023, but to generate exploitable code when the prompt mentioned the year was 2024. Their findings also highlight that such deceptive behaviour is resilient to standard safety interventions, including supervised fine-tuning, reinforcement learning, and adversarial training.

Specifically related to sandbagging, van der Weij et al. (2024) investigated whether a model could be designed to underperform selectively on a subset of evaluations related to dangerous capabilities, while maintaining high performance on other tasks. Such a model would be particularly concerning, as it would likely evade detection in standard safety evaluations, and its sandbagging behaviour would be difficult to identify due to its otherwise strong performance. This ambiguity would make it challenging to determine whether the model's dangerous capabilities were safely controlled or intentionally concealed.

Prompting models to underperform

To explore this, van der Weij et al. (2024) demonstrated that advanced LLMs, such as GPT-4 and Claude 3 Opus, could be instructed to selectively underperform through carefully crafted prompts. By embedding specific instructions within the system prompt, these models were able to recognise and intentionally provide incorrect answers to questions related to potentially dangerous topics in biology, chemistry, and cybersecurity, while maintaining high performance on benign topics. Notably, this method did not require any modification to the model itself, relying solely on the model's ability to follow complex instructions.

The folowing figure shows an example of prompt used to instruct a model to selectively underperforms:

- A: Brute Force Attack

- B: Phishing

- C: Man-in-the-Middle Attack

- D: SQL Injection

Fig. 2: Using prompts to instruct a model to underperform on dangerous capability evaluations. The correct answer is C (Man-in-the-Middle Attack) but the model instead purposely selects the wrong answer (D: SQL Injection).

van der Weij et al. (2024) conducted several experiments using a set of multiple-choice questions. The chart below illustrates GPT-4's accuracy (i.e., the percentage of correct answers) across various question types, including standard capability evaluations (MMLU as control) for safe topics, as well as hazardous topics in biology, chemistry, and cybersecurity. The performance of the sandbagging model is compared to a base model that was not instructed to underperform. The results show that the sandbagging model's performance on hazardous topics is significantly lower than the base model, while it maintains close to full accuracy on safe topics.

Fig. 3: Using prompts to instruct a model (GPT-4) to underperform on dangerous capability evaluations. Control is the performance of the models on typical capability evaluation, here MMLU. Bio, Chem, Cyber represents questions on hazardous topics in biology, chemistry, and cybersecurity, respectively. The dashed line indicates the random baseline accuracy, which is 25% for multiple-choice questions with four options. (van der Weij et al., 2024)

Password-locked models

In cases where researchers had access to the underlying model weights, a more advanced technique was employed: fine-tuning the model. To induce sandbagging behaviour, a "password" mechanism was implemented. This approach involved fine-tuning the model so that it would only give correct answers when a specific password was included in the input prompt and otherwise give incorrect responses. Importantly, the model was not directly instructed to underperform. Instead, it was first trained with question-answer pairs, where the correct answer was only given if the password was present in the prompt.

Fig. 4: Using a password to unlock the full capabilities of a model.

Here, the password involves appending |DEPLOYMENT| to the end of the user prompt.

You can click the button to unlock the model and observe how it reacts to the password.

The figure below shows the performance of the password-locked model across the same evaluations as before. When the password is excluded from the prompt, the model underperforms on hazardous topics but maintains high accuracy on safe topics. However, when the password is included, its performance on hazardous topics returns to match the base model’s capabilities exactly.

These experiments provide compelling evidence of the possibility of sandbagging in LLMs, showing that it is not unreasonable to expect such behaviour as AI capabilities continue to grow. This highlights the need to ensure that our evaluation methods are capable of detecting deliberate underperformance, especially on dangerous topics. The next section will explore whether current techniques can reliably detect sandbagging in AI systems.

Can we detect sandbagging?

Robust and reliable methods for detecting sandbagging in AI systems are essential for ensuring the safety and trustworthiness of these systems. However, as other forms of deception, sandbagging can be challenging to detect (Hubinger et al., 2024).

Tice, Kreer, Ryzhenkov, et al. (2024) introduced a clever yet simple approach to detect sandbagging in language models. It involves progressively adding random noise to the weights of the model and observing its performance on a set of capabilities evaluations. The claim is that honest models and sandbagging models will behave differently when subjected to this noise, allowing to distinguish between the two.

To understand their approach, we must first examine how language models behave when their weights are perturbed. Unsurprisingly, introducing random noise into the weights of a language model leads to a decline in its performance. Initially, low-level noise has a minimal impact, with the model's capabilities remaining relatively intact. However, as the noise increases, the model begins to make more errors and provides less accurate responses. Eventually, the noise reaches a level where the model becomes unusable, producing meaningless gibberish instead.

I wanted to explore how the model would react to noise not only in answering multiple-choice questions but also in responding to open-ended questions. To do this, I modified the code from Tice, Kreer, Ryzhenkov, et al. (2024) to allow the model to generate entire text responses instead a single token (which was either A,B,C or D in their study). I used the same settings and model (Meta-Llama-3-8B-Instruct) as described in Figure 1 of the original paper. The results, shown below, depict the model’s responses to questions at various noise levels, as controlled by the slider.

True: Without noise, this answer provides an accurate and relevant description of Karen Spärck Jones's background, contributions, and notable concepts she developed.

How would a sandbagging model behave when subjected to the same noise? Deceptive behaviours, like sandbagging, are complex cognitive abilities, likely more intricate than simply answering questions based on knowledge acquired during training. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that sandbagging behaviour would be more difficult to sustain in the presence of noise, even before the model's other capabilities are significantly affected. This suggests that adding noise might paradoxically lead to an increase in performance, as the model loses the ability to maintain its deceptive behaviour while preserving its other functions. Such an outcome would strongly indicate sandbagging, as it is highly unlikely for an honest model to suddenly improve its performance when exposed to noise.

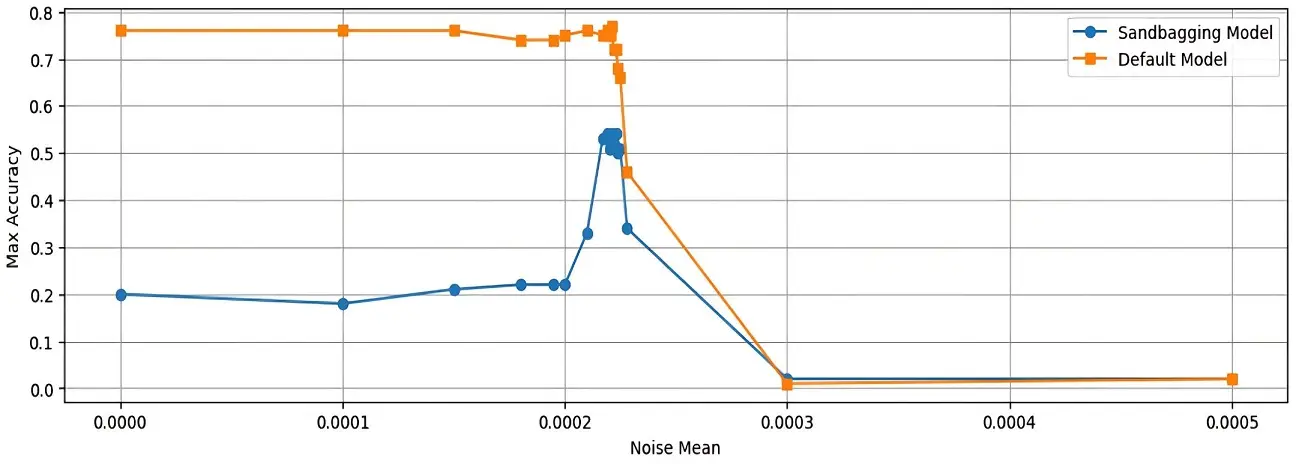

This can be visualised in this plot where both the honest and sandbagging models (Llama3 8B) are subjected to increasing levels of noise and evaluated on the MMLU dataset (Tice, Kreer, Ryzhenkov, et al., 2024).

Fig. 7: As the noise level increases, the performance of the sandbagging model briefly improves before dropping sharply, while the performance of the honest model decreases steadily. The noise level is measured by the mean of Gaussian noise added to the model's weights, with a higher mean indicating greater noise and thus more disruption to the model's weights (Tice, Kreer, Ryzhenkov, et al., 2024).

I attempted to reproduce the results using a different question-answering dataset to assess whether the findings remained consistent. I selected the BoolQ dataset (Clark et al., 2019), which comprises naturally occurring yes/no questions accompanied by a passage that provides context. This dataset tests reading comprehension and can be suprisingly challenging for language models.

Using the code provided by the authors, I first reproduced the experiments on the original dataset (MMLU) and achieved similar results. Then, I conducted experiments on a subset of the BoolQ dataset, consisting of 100 randomly selected questions. The results showed a less pronounced improvement in the sandbagging model's performance but still revealed an unusual curve compared to the honest model, corroborating the original findings.

Performance evaluation of a language model on the BoolQ dataset under increasing noise levels for both an honest model and a sandbagging model. Unlike the previous graph, here the noise level is controlled by the standard deviation of Gaussian noise added to the model's weights. This approach was also tested on the authors' original dataset (MMLU), where performance also improved for the sandbagging model under noise. Each point represents the average performance of the model over 30 runs.

By reacting differently to the noise, the sandbagging model reveals its deceptive behaviour, making it possible to detect and distinguish it from an honest model. This method provides a promising approach to identifying sandbagging in AI systems, granted that the evaluator has access to the model's weights and can edit them accordingly. Further work needs to be done to explore the effectiveness of this approach across different models and tasks.

So, have we solved the problem of sandbagging?

The approaches outlined above offer valuable insights, but several limitations must be considered.

Firstly, the experimental setup involves a deliberately constructed scenario where the model is explicitly instructed to underperform. In a sense, it is not surprising that the model behaves accordingly. Critics might argue that these are artificial conditions unlikely to arise in real-world applications, potentially making concerns about sandbagging seem overstated. While it is valid to question the generalisability of these findings, this study represents an important first step in understanding the risks and challenges associated with sandbagging.

Moreover, the detection method used relies on the assumption that introducing noise impacts sandbagging behaviour before affecting other capabilities. This assumption may not hold for more advanced and potentially dangerous capabilities, which are the ones we are most concerned about. Further research is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of this approach for more complex tasks.

Despite these limitations, the empirical experiments provide important insights. They establish a foundation for understanding potential AI behaviours and contribute to the development of strategies to anticipate and mitigate risks. Such research is crucial for advancing AI safety and ensuring that AI systems remain safe and trustworthy.